A SELF HISTORY CHAPTER 8

A series of weekly published chapters by Ken The Pen written in a humerous and informative style.

A SELF HISTORY CHAPTER 6

HOLLANDWOOD MY COUNTRYSIDE EDUCATION. HISTORY MEETS LITERATURE.

A SELF HISTORY CHAPTER 7

REPERCUSSIONS AND CATCH UP. LURGASHALL LAND OF ADVENTURE.

A SELF HISTORY CHAPTER 8

SLUICES, SLIDES, WAGTAILS & WATERMILLS

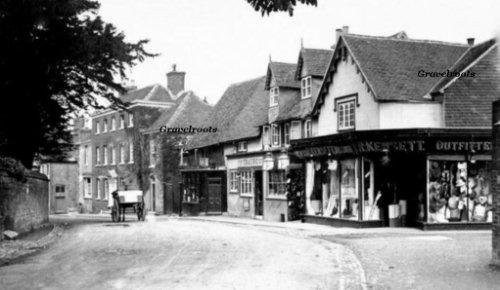

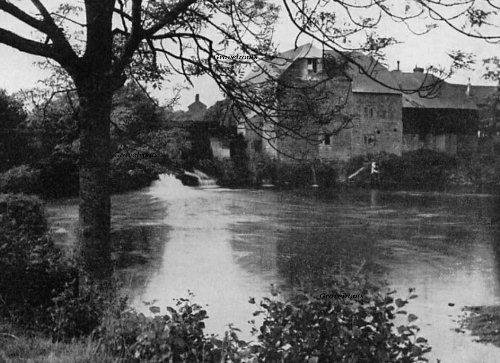

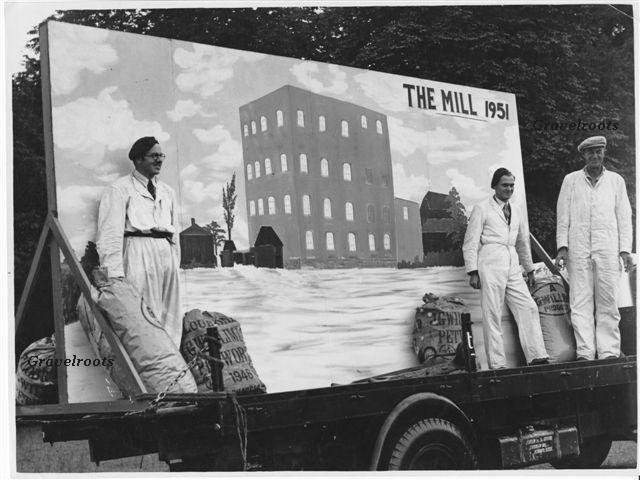

On the right-hand side of the lane which led to the Watermill was a little island jutting out into the lake and it was here that the sluice gates had been positioned and built. The lane itself passed over a low bridge which enabled water to flow from the lake and under the bridge before running down a tiled gully for several yards before cascading down into a small pond to the left of the lane. The pool on the left was about 20 foot below the level of the main lake and effectively joined other streams in creating a small river which led away across the fields. The leets from the main lake which effectively powered the Watermill, then also became small streams which led into the lower pool ; the sluice gates were only used to control the main lake if the water level became too high. The cascading gully was therefore quite like a water slide that you might find at amusement parks and it was this that had given me the idea of creating our own special water chute. Tommy and I experimented with twigs and branches varying in size and structure before lowering the wooden door carefully as far as we could off the top of the bridge before releasing it and then retrieving it and making the arduous journey back up to the bridge to repeat the experiment. This went on for a couple of days because the work was quite arduous and we had to make a couple of adjustments and repairs to the door before we felt that everything was right. At last all was ready my father was working in the upper fields, my mother had walked into Lurgashall village to do some shopping and my sister had gone with her. Tommy turned up and we went and retrieved our hidden surf boat, took it to the bridge and carefully lowered it over the side before climbing over the abutment and pushing it to land on one side of the gully. Fortunately it lay back against the gully wall and was prevented from moving away by a couple of rocks on the gully floor while we climbed down into the running water. Tommy stood at the back of our makeshift boat while I clambered onto it and moved myself to the front so that he could climb on behind me, but unfortunately he released his hold in order to put his hands onto it and without his restraint the door surged forward. The downward slope of the gully, aided by my weight at the front and the water flowing from behind caused the door to start careering toward the drop ahead but fortunately the boat tilted and I fell off into the leet clinging desperately to the side walls as the boat upended and disappeared from sight. Scrambling back up to our starting point I rejoined Tommy and we climbed the bank before making our way down the slopes of the cliff till we came to the side of the lower pool. Our boat had bounced off outcrops of jagged rocks as it fell about twenty foot to the pool below, the door had been broken into pieces; I had had a lucky if accidental escape! More importantly however we made two interesting discoveries, firstly the central abutment supporting the bridge had a ledge about halfway down upon which were scattered the remains of a wagtail’s nest. More importantly as we made our way from the lower pool across the fields toward my home, this time from the rear of the Watermill rather than along the lane which was the route we normally took, we saw a broken window that we had never seen before, it was partly hidden by the huge water wheel that had once powered the Watermill. Our disappointment from the failed expedition was immediately forgotten, we were soaked and needed to go back to my house to dry out hopefully get some food if my mother was back from the shops but a far greater adventure lay in store, Tommy would be coming back again tomorrow.

The next day Tommy turned up early so my mother invited him to join me for breakfast and since we did not want to cause suspicion by appearing too eager to go out we had boiled egg and fingers and a cup of milk then helped clear up before saying our goodbyes. Ten minutes later we had walked along the Lane and made our way down to the lower pool on the right, then doubled back across the fields to the back of the mill and climbed up the side of the waterwheel where we managed to lift up the latch of the broken window and let ourselves in. We explored the inside of the whole of the middle floor where the huge millstones were lying one on top of the other and then climbed up the stairs to one side of them to see what we would find. The upstairs was like a row of large wooden boxes on each side of the Watermill with a long corridor going down between them from the front to the back of the Watermill. Some of the boxes had sacks and clutter in them but about half of them were actually still half full of corn as if they were still just waiting to be used. We went back down the stairs and then across to the side again and then down the next of stairs until we found ourselves on the mill wheel floor where the machinery and all the cogs and gears were still in place along a huge metal bar coming in through a hole in the side of the mill to the huge water wheel outside. We peeked out of a window up and down the lane to make sure that nobody was around and then went back to the door on the ground floor, it had two bolts, one up near the top and the other near the bottom. I tried pulling one of the bolts but it wouldn’t move so Tommy tried the other one but that didn’t move either so I went and found a bit of wood and hit the bolt a couple of times and at last it moved. Tommy had a go at the top one because he was a bit taller than me and that one slid open as well so I ran back upstairs and looked out of the window to make sure that nobody was around, then went back downstairs and we pulled the door by its handle and to our surprise and delight it actually opened! We pushed the two bolts back into their sockets then went back up to the window and climbed back out, slid back the latch and climbed back down the side of the waterwheel. We were so elated but also afraid that somebody might have seen us or might see us now so we played around on the island on the other side of the Lane and then made our way back to my home where we played in the Orchard for while then got some hooks lines floats and a few worms before we went for a walk along the side of the Lake until we came to my favourite log and stayed there fishing until it was time for Tommy to go home. We had agreed not to go back to the Watermill for a few days in case anybody might have seen us so we just had to bide our time. The excitement but also the tension were as thrilling to us as our new secret discovery. One other little twist of fate had happened around this time was that although I was actually still only ten years old I had taken my eleven-plus exam and had passed the exam so would have gone ironically to the nearest grammar school which might have been in Petworth or in Northchapel. Since my sister had not passed her eleven plus exam she would have gone to a secondary school anyway so we would still have been parted. Because my father resented the idea of grammar schools and all that he thought they represented, he refused to allow me to go there. Sometimes I would be out with my mum and dad and we stopped to talk to people and somebody would say “When’s your little clever clogs going up to the new school then?” Then my dad would just say “He’s too smart for his own good, he won’t be going there.” But I didn’t know what they were talking about and I never knew that I had been given the opportunity anyway, so I never went to grammar school. Tommy and I, along with his older brother Albert got hold of some 4.10 and some 12 bore cartridges, possibly from the farm or perhaps even my father or theirs, after we had found a way to fit them into holes in a barn half way around our side of the edge of the Lake. We cut little slots to look through and would fit a cartridge into the hole near it, then one of us would look through the slots while someone else would hold a nail against the end of the cartridge. When a look-out saw a duck or a crane he would quickly shout and the person holding the nail would hit it with a hammer and sometimes the cartridge would fire hopefully to shoot a duck! It was a dangerous and exciting game and of course an impossible task, though we were always sure that one day we would hit one. How we could have got out onto the Lake to retrieve it hadn’t been thought about and after a few bruised fingers and a zero success rate we eventually lost interest. In the meantime two of the young lady teachers at our primary school had become good friends and because they both caught a bus back home after school they decided to take any of us that were interested out for walks in the lanes around the village before they went home. We loved the idea and they always had plenty of eager children to accompany them once they had sounded it out with the parents, Babs and I were two of their staunchest supporters all through the spring and early summer, but lots of parents were glad of these “free” childminders which meant that they could carry on with their own work or preparing evening meals. This two-way activity resulted in parents providing fruit from the orchards, sometimes sandwiches or cakes cooked at home which the children could share and drinks of milk or water which they brought in to school in the mornings and then children could return in the late afternoon as far as the containers like bottles or flasks were concerned. Babs and I were leaders in this respect because we had loads of fruit in our garden and could get lots of milk from the farm because we helped a little bit with the milking. Lurgashall was a small village where everybody knew each other and we had a close knit community, which sadly is now far less common. Ironically what should have been one of the bastions of village life in that age, was sadly missing at least from our perception. I remember going to the church with my sister and some of our friends to see what it was all about, admittedly we arrived after the service had commenced but when you consider that my sister and I and the Thomas children lived quite some distance from the village and that the children living within the village would await our arrival before going in, it was hardly fitting for the vicar and choirmaster to berate us and for the tutting and glaring looks of the congregation that followed. A fortnight later we repeated our pilgrimage by prior arrangement with children from the village, but again we were chastised and this time asked to leave even though it was raining outside when we got there. It was our last attempt to go to the church and had been meant purely as an act of inquisitiveness and wanting to know the purpose of people going to church on a Sunday.

Suffice to say that none of us went to the church again and in fact what we came to regard as a justification and a victory for us was the fact that the American girl who had so smitten me for months, decided to join us in rebellion by not going to church with her family the following week and although they entreated her to go, they were gracious enough to accede to her wishes on a point of principle. After that she compromised with her family in that she attended mid week services with them but at weekends would join our group which was now meeting in the Lane leading to the Watermill. I was so delighted that I took her into, and for a tour around, the Watermill which really thrilled her to such an extent that Tommy and I realised that we had a potential moneymaker and so we offered on a trial basis to let favoured children into the Watermill for a payment of a penny. Inside, they could go onto the ground floor and look at all the gears and cogs and machinery and look up at the chute where the corn came down to fill the sacks, then up onto the middle floor where the giant millstones ground the corn, and then onto the top floor which became their favourite simply because you could jump into the great storage containers which had once held and to some extent was still holding piles of grain which had never been ground. We also let them look out of the side window which showed the giant water wheel which we had originally climbed to gain entry on our first visit, though nobody was allowed anywhere near the waterwheel. Of course the word spread and more children wanted to visit which quite delighted us for some time until a couple of envious children who could not afford the penny told their parents and then somebody told the farmer who in turn told my father, asked him to seal the doors again. I got a clip around the ear and a demand for any of the money that I still had left from my guided tours; he couldn’t demand anything back from Tommy but it was the end of our business enterprise. One of the things that had come from our intended surf slide was that I had noticed the remains of a wagtail’s nest on the bridge abutment and so each day on the way home from school I would look over the side until one day I was rewarded with the sight of a wagtail sitting so I clapped and waved my arms around until it flew away. There in the nest were four eggs so I carefully climbed over onto the abutment and took out one egg for myself which I held carefully in my mouth I climbed back up to the road. I put the egg up into my bedroom and walked back to the bridge to see that the wagtail had returned so didn’t feel guilty; when my father got home I showed him the egg and he said that it would addle unless I blew it so he showed me how to do it and now I had a new hobby. My father had a dual personality, he could fly off the handle at the smallest of things, but could also show the greatest patience and helpfulness in explaining things to me if the mood so took him. I then began bird nesting where I would take only one egg from a nest and never the same egg from any other nests, my egg collection increased in leaps and bounds and I was observant enough to know where to look from hedges, to bushes to trees, or even into, or on top of, the ground, and I also never told anybody of where any nests were. From the wagtail I progressed to hedge sparrows, tree sparrows, house sparrows, blackbirds, mistle thrushes and song thrushes, blue tits, coaltits, longtailed tits, bullfinches, chaffinches, reed warblers, coots, moorhens, pheasants, partridges, pigeons, plovers, woodpeckers, ducks, geese, kestrels and falcons, swifts and swallows, housemartins and turtledoves, rooks and crows and starlings and buntings, greenfinches and goldfinches and of course the much loved Robin redbreast; the list goes on and I could easily fill a page but then having finished and moved on, another would come to mind so I’ll leave it there. I collected birds eggs for the whole of my time at Lurgashall, I even took them in to show to my class and my two favourite teachers asked me if I would let them show them to the other classes and because I liked them because they had always taken us for walks, I happily obliged so the whole school got to see them. Apart from the walks that they took us on one of the teachers got hold of some silkworms from somewhere and brought them into her class and set them up in a glass case and because she happened to be my class teacher I was able to look at them daily. They didn’t actually do very much but she told us how hundreds of years before a lady from China on the other side of the world had noticed them laying a string which could be woven into silk which is unlike any cloth that had ever been made before. The way she told the story impressed me so much that I went to the school library to see what I could find out about China and about silkworms. One of the other teachers in the library told my teacher and she came to see me after school before I went home to take me into the library and help me look for information, so that formed a bond between us and I became one of her favourites as she was one of mine. There were no bathrooms in houses at that time, certainly not in farm cottages or probably anywhere around Lurgashall, so once a week we all helped in filling the bath with hot water from buckets and kettles on the stove, which was the start of a weekly routine which was both exciting and yet, on my part at least, not something to be looked forward to. Once it was filled, Trevor, Johnny, Colin and I were all sent out of the room so that my sister could undress and then get into the bath and once she had been dried and then wrapped into her bedclothes, Colin, being the youngest and therefore the smallest was put into her bath which now held used water, he was then removed dried and dressed for bed while some of the water was scooped out and tipped away before more hot water was added. Johnny was next, dried and dressed while more water was partially replaced and Trevor took his place and the whole process repeated. I, being the oldest boy was the last to have the pleasure of my weekly bath and depending upon how long the others had taken, and how diligently the saucepans had been refilled and reheated over the stove, would step into a very hot, or a very lukewarm and quite murky bath. At least we did always have a bath once a week and when I mentioned it to various of my friends I was amazed to learn that most of them felt quite fortunate to have a bath once a fortnight or in some cases once a month, to stand naked in the kitchen while they were rubbed down with a flannel dipped into the warm water in the sink! Before I knew it my next birthday came around and I took my first steps into the world of technology, my parents bought me a film projector which was a giant leap into the future although I didn’t know it at the time. I can’t remember the exact process but you had to hold a projector with your left hand and turn a winding handle with your right and the film would be played on the wall in front of you. It was quite jerky depending upon how well you turned the winder and we all used to stand in our hallway in the early evening so that we could see it to its best effect; but it was absolutely magic and the best present I had ever been given. I often think back to things like that and wonder how much they would be worth nowadays. In the summer we collected raspberries, strawberries, blackcurrants and red currants and my mother bottled it all to store away or used it to make jam, and then in the late autumn we collected the fruit from our fruit trees and wrapped the apples in paper which would last well into the winter. Looking back now I regret the loss of such skills in the lives of many modern day people, though of course the ability to purchase fruit all through the year and mainly from abroad removes such a necessity. We also went out into the countryside and picked walnuts, chestnuts and hazelnuts to store away as well as the ubiquitous horse chestnuts or (conkers) which was one of the big games played in schools and everywhere really by the children of the day. As Christmas approached we decided, along with the Ailwood’s to go and get a Christmas tree for each of us and for the Thomsons who were now on completely friendly terms with us. There were no trees close to where we lived so we had to walk all the way into Lurgashall to meet up with Tommy and then along a road behind our school where he had never been before but which the Ailwood’s knew well. We had a couple of saws and an axe though I can’t remember from where, and we went along until we came upon some fir trees which had suitable tops; two girls stood or played and ran around while we boys climbed two different trees and started cutting. Every so often we got warning calls from the girls that there were people around so we had to stop and try to keep hidden. After some considerable time Tommy and Albert on their tree and myself and another boy whose name I forget, both managed to cut through our treetops at the same time where with a tremendous crash they both fell from the treetops and smashed onto the floor below. We were all panicked by the noise and shot down the trees with our axis and saws, and fled the scene as fast as we could. About half an hour later, leaving our tools hidden on the leaves and amidst the bushes, we made our way gingerly back to where we had been, but both of the Christmas treetops had disappeared. We were too scared to start again and worried that other people might be waiting for us and so we made our way back to Lurgashall with our tails between our legs. A couple of days later my father came home with a Christmas tree tucked under his arm which had been given to him by one of the Anstee brothers, it was actually their normal Christmas practice.

CONTINUING READING A SELF HISTORY CHAPTER 9

CONTINUING READING A SELF HISTORY CHAPTR 10

Receive New Chapter Email Notifications

Would you like to be informed of when new chapters are published? Simply use the contact form to the right and we will keep you posted. We promise not to bombard your email in box with anything else.